Is a Building Complicated or Complex?

Posted by Steve Weinbeer

Categories

March 22, 2023

Is a building complicated or complex? Spoiler alert: The building is complicated, and the process build it is complex. This difference is subtle, yet significant. Our approach to designing and construction of buildings pivots on our understanding of the difference, and the widespread interchanging of these terms causes dysfunction in the buildings industry.

Before we go any further, let’s start with a definition of complicated and complex systems.

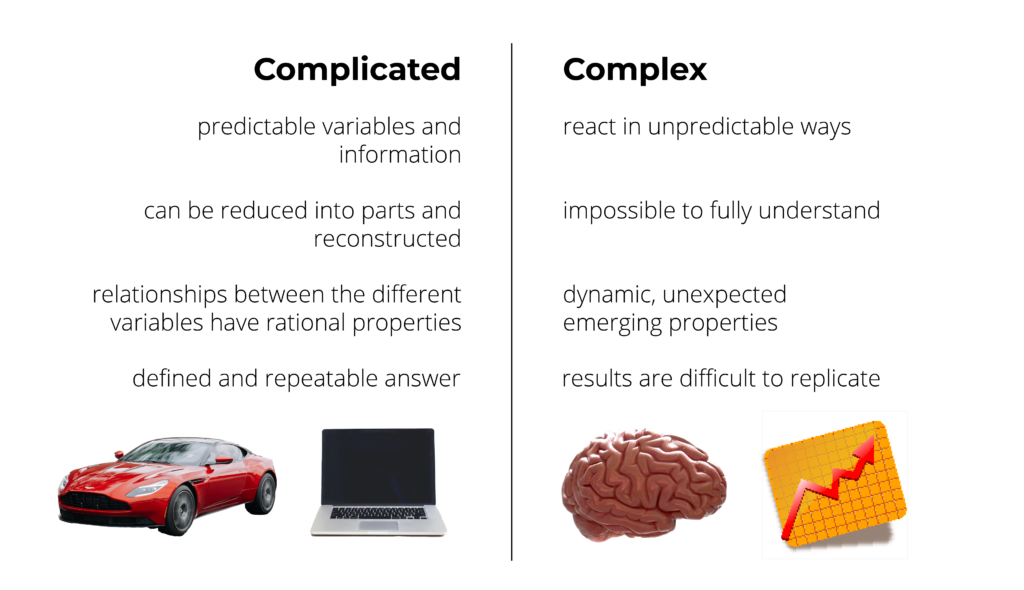

Complicated systems refer to systems with predictable variables and information. The system can be reduced into parts and reconstructed with an understanding of each relationship. The relationships between the different variables have rational properties. The system is solvable, with a defined and repeatable answer. A computer, a car, an excel macro, and a computer operating system are “complicated”.

In contrast, complex systems react in unpredictable ways. The relationship between its parts is impossible to fully understand. The system is dynamic and creates unexpected emerging properties. The results are difficult to replicate. The human body, brain, interaction with others, ecosystem, and stock market are “complex.”

In its final constructed state, a building is complicated. The building can be reduced into parts, each with a defined relationship. It has architectural, mechanical, electrical, and structural systems assembled like a jigsaw puzzle. A building can be “solved.”

But while a building in its end condition is complicated, the building process is complex. We can try to build the same building on a different site with the same plans and team, but completely different issues will arise. Change orders, Requests for Information (RFIs), drawings revisions, schedule delays, and cost overruns are all emerging properties of a complex system.

When we understand that the building process is “complex”, we can respect the unique character characteristics of a complex system and work together to achieve high performing buildings more consistently for our community.

Fast is Slow with Buildings

Stephen Covey has famously said, “With people, slow is fast and fast is slow.” His quote describes the need to go slow when relating with people. Human interactions are not like dealing with things in your life. You can automate and optimize material things, but not people. People and their relationships to one another are complex. People’s actions are guided by their previous experiences and cognitive biases. People are unpredictable.

The process bringing buildings to life involves a great deal of relationships—and, in turn, is complex for that very nature. When we fail to recognize this process as complex puts the focus on speed: how fast can we get from start and finish? Meanwhile, we miss the mark on strengthening relationships and build team culture. Yet, those are the very things that allow the team to communicate better, empathize, and work together. Investing in a team’s understanding of each other’s strengths, communication styles, and personalities is non-monetary capital that can result in future monetary savings.

This is hard for an owner to see, at least in the beginning. A few years ago, we were on the team for the construction of a new $30 million school. At our first Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) “big room” meeting, we gathered 30 people together; a representative from all the major design and construction disciplines was there to represent their unique scope. Unsurprisingly, the client was in shock at the cost of that meeting. Roughly speaking, if each person charges out $160/hr, this 3-hour meeting cost them a whopping $14,400. A single meeting, with nothing tangible to show at the end.

That is, until we fast forward to the end.

The project came in ahead of schedule and under budget. The early and continual investment in relationships throughout the project resulted in money saved through the process. A team culture built on trust resulted in the right decisions made early having exponential benefits downstream. We were even able to redirect the money saved into the building to cover several of their wish-list items. We all win when we trust the process together.

Risk Sharing Through Transparency

Risk is a by-product of a complex system, and contingency how the buildings industry’s addresses risk. Buildings involve hundreds, if not thousands of work scopes, and each scope gets a contingency.

Conventionally speaking, each discipline keeps their cards close to their chest, with an “each man for themselves” approach to contingency. It’s not meant to be malicious—it’s easy. Why be open and transparent about your project scope, budget, and financials with anyone else on the team? It’s not their business.

And yet, with this approach, each discipline tends to inflate their contingency (to cover their own base), escalating the overall project cost, and, in the worst cases, projects get shelved. Surely, there’s a better way.

At a previous firm, my business partner and I faced this challenge. We were asked to interview for our first IPD project. Our proposal was good enough to get short-listed to one of 3 structural teams; we were the underdogs with no IPD experience at the time. We had to convince the interview panel we had technical proficiency and would be a valuable addition to the project team.

We spent days and nights preparing for the interview. We brought in visuals and lessons learned from previous projects. We wanted it badly – we were drawn to IPD. We gave it our all, and near the end of the interview, we had successfully won over the panel.

And then, came the last question.

“Will you have any issue getting this project approved by your legal committee?”

We didn’t know. Having never done an IPD project before, we didn’t understand how they worked contractually. But we didn’t want to throw away the interview.

“Leave it to us, we’ll make sure it’s not a problem.”

Not knowing what we just committed to, we spent two weeks combing through different levels of management trying to get approval. We found a lawyer experienced in this type of project delivery, but they were across the country and dealt exclusively with projects in the United States. Finding someone that understood the risks and was willing to sign off on the poly-party contract and open the company’s project financials was extremely difficult.

This is a challenge many companies face, even before the project begins. However, once the financials are shared, the game changes. Scope can be changed, properly discussed, and adjusted on the fly to the most suitable party. Scope isn’t counted twice, and therefore, contingency isn’t counted twice. It sets a healthy precedent for the project: when we prioritize honesty and working together, everyone succeeds.

A Change in Identity

“The strongest force in the human personality is the need to stay consistent in how we define ourselves.” Tony Robbins

Tony Robbins, a well-known and prosperous life, and business strategist, believes that a strong force keeps us consistent with how we see ourselves. For example, when we label ourselves Engineers, Architects, and Contractors, we see the world through that lens—a helpful perspective to bring to a project, but also a limited one.

None of us can be simplified to just one role or identity. We have roles on a project, in the office, and in our everyday lives. We may be parents, mentors, team leaders, employees, volunteers, and many others. On a project, it is helpful to see the bigger picture.

On the same school project I mentioned earlier, we established an identity that was bigger and more holistic than any one of our own disciplines. We were engineers, architects, and contractors—of course. But that was secondary to why we were all there: to create space for the next generation of elementary and junior high students.

We were empowered to make decisions on behalf of the entire team. In this environment, an electrical trade can provide input to an architectural detailer, and a drywall trade can provide advice on the location of a school playground – both of which happened on this project.

Identity drives behaviour and helps fill inevitable scope gaps. Have fun with it. See yourself as a “Space Creator”, or “Lifestyle Designer” and watch how this affects what you focus on and how you contribute to the team.

So, start treating buildings as complex…

We must start considering buildings as “complex” and educate others to respect the system’s unpredictability. We need to change our approach. Focus less on standardizing and optimizing processes, and instead create an environment that rewards flexibility. Go slowly to build trust, share the risk through transparency, and adopt a holistic identity. Our buildings depend on it.