Resilience: Embracing and Overcoming Challenges

Posted by Jeff Hung

Categories

November 30, 2022

Structural engineers spend a lot of time thinking about resilience—the capacity of a material to return to its original form after being bent, compressed, or stretched. We meticulously measure the resilience of the materials we work with. We try to maximize it in the structures we design. In fact, the pursuit of the most possible resilience within a given set of design constraints isn’t a bad way to describe the profession.

In the world of building design, structural resilience can be extremely difficult to achieve. The environmental stresses that strain and eventually degrade materials are inevitable. Over the past century and a half, we’ve figured out how to build increasingly taller, more beautiful, and longer-lasting structures. It’s a challenge that I continue to enjoy throughout my career–and along the way, it’s given me a lot of insight into resiliency in everyday contexts.

Embracing challenges to build resilience

You don’t have to be a structural engineer designing buildings to see the importance of resilience in daily work. Clients challenge you. Project scopes change. Proposals don’t succeed. “Failure” is not a word that anybody likes to hear, but personal failure is something we need to face and accept more often than we like to admit.

At Eng-Spire, we believe that this kind of failure is not just inevitable but necessary. The only way to never fail is to never attempt the challenging or the ambitious. Or, as Denzel Washington puts it simply: “If you don’t fail, you’re not even trying.”

When we learn from our mistakes and the mistakes of others, failure builds resilience. Failure can fuel success. This is why we prize resilience, in all its forms, so highly at Eng-Spire. The only way to measure the resilience of a material is to push it up to the point of failure. We think the same is true of people, so we love to work with clients that challenge us and stretch our way of thinking and doing.

Pushing the limits of structural design

When I think of resilience and embracing challenging projects, the Winspear Completion Project immediately comes to mind. The Francis Winspear Centre for Music is an iconic arts facility in Edmonton, and the original design from 1997 is still highly regarded as one of the best acoustical performance spaces across the country. The opportunity to help build an 80,000+ square-foot expansion to the original structure is once in a lifetime.

Rendering courtesy of Andrew Bromberg Architects, in partnership with TBD Architecture + Urban Planning

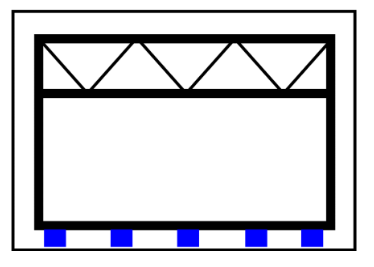

The state-of-the-art expansion, envisioned by lead architect Andrew Bromberg in partnership with TBD Architecture + Urban Planning, features a 550-seat multi-use acoustic hall intended to provide the Arts District in the heart of downtown Edmonton with a brand-new performance space: the “Music Box”. As you can imagine, the acoustic performance of the Music Box is critical to the success of the project; the client requested a total acoustic separation between the performance space and the rest of the structure. This would be the first of its kind in Edmonton.

While I am deeply familiar with the fundamental engineering principles to make this happen, what the client was asking for is cutting-edge and highly specialized. Indeed, this was pushing the limits of structural design. In essence, we would have to build a “box inside of a box”. So, along with spending hours in research and reading successful case studies of acoustic isolation in performance spaces across the world, I tapped into my network.

My colleagues and I reached out to various structural engineers, architects, and contractors that we have worked with over the years. And after several connections and recommendations, I had the great privilege of connecting with a structural design expert based out of the New Jersey office of Thornton Tomasetti.

He was not only able to apply his expertise and experience in high-rise buildings to help solve this challenge, but also had a great deal of interest and enthusiasm in helping me learn more about the structural design process. He generously connected with me and answered question after question, equipping me to tackle the acoustic isolation design with confidence.

Of course, this experience taught me a lot about acoustics and how to design a structure to optimize it. But more importantly, this challenge stretched me beyond what I was capable of on my own. By embracing the challenge, recognizing the limits of my skillset, and reaching out to a fantastic network of professional colleagues, I learned that I could seek out and find like-minded people who would be willing to share their expertise.

Resilience & Rest

There’s one more aspect of resilience that I think is critical to the conversation: bouncing back from stress. Having a mindset of resilience means that we strive to build safe spaces for our communities, our clients, and ourselves. We see value in taking time to recover, dreaming big and falling short, working hard and resting even harder, and rethinking the way we work. When we moved into our new office, we decided that it was important to design spaces not only to concentrate and collaborate–but also to designate spaces to chatter and be simply present with colleagues that have become friends. If you haven’t read Steve’s blog featuring our new office and some of the ideas we’ve been experimenting with, go ahead and check it out!

Why it Matters

We seek to build resilience in every aspect of ourselves because we see direct lines between them and the kind of resilience that keeps buildings from collapsing and bridges from falling down. We believe that setting up a positive feedback loop where social and personal resilience leads to more structural resilience. Ultimately, it’s what helps us build exceptional buildings and bring great communities together.